A Short History of Rice Cultivation in Louisiana

- depradine175

- Nov 10, 2025

- 5 min read

What is the relationship between rice and wine?

Well, there isn't much of a relationship.

Why is there an essay on the history of rice in Louisiana within a mead website?

It was part of a larger essay on African Americans, Louisiana, and the wine industry that I started in 2012.

Go to any music festival in southern Louisiana and you are bound to find a vendor selling boudin, jambalaya, rice dressing, or white rice as an accompaniment to a sauce piquant, fricassée, or gumbo. I think it is safe to assume that few people ever think that the state's rice industry was created three hundred years ago as a way for Louisiana to have a local, home-grown source of carbohydrates.

Louisiana's French colonists did not have experience growing rice in Quebec, Acadie, or in western Europe. Why? It is too cold for the rice plant to survive in Canada or in western France.

Spanish colonists from the Canary Islands did not bring rice cultivation techniques to southern Louisiana either.

Enslaved West Africans brought the knowledge to grow a reliable cereal crop to Louisiana that benefited the French and Spanish colonists. The large colonial settlement of Louisiana might have been different if the colonists did not have a ready source of carbohydrates besides corn. This is my attempt to give those enslaved Senegambian men and women credit for bringing their knowledge to Louisiana.

Early Beginnings (1710–1717)

Rice has nourished Louisiana residents for nearly three centuries. Unlike many cereal grains, rice thrives in the state’s subtropical climate. As early as 1710, Paul Phélypeaux, Duke of Pontchartrain, and Inspector Pierre d’Artaguiette recognized Louisiana’s swamps and floodplains as ideal for rice cultivation. D’Artaguiette described rice as the “small farmer’s dream” for its low cost and good returns.

But the colony lacked two essentials: rice seed and people skilled in its cultivation. Twice, in 1710 and 1712, French officials appealed to Spanish governors in Havana and Veracruz for rice seed. Both requests were denied, although flour and livestock were sent to the France's Gulf Coast colonists. The Spanish likely saw withholding rice seed as a way to weaken the French colony.

By 1717, Louisiana’s new proprietors, the Company of the West, demanded self-sufficiency and exports of crops like tobacco, indigo, rice, and corn. Yet with only 700 European colonists and little interest in farming, Louisiana still had no rice industry.

African Seeds and Knowledge (1719 Onward)

In 1719, rice arrived from Africa along with the enslaved people who carried the knowledge to grow it. Two company ships, L’Aurore and Le Duc du Maine, transported captives from the port of Whydah in modern-day Benin, bringing both seed rice and skilled farmers.

Between 1719 and 1769, nearly 6,000 Africans arrived in French Louisiana through the port of New Orleans. Most came from Upper Guinea or Senegambia region of West African. Many of these captives were members of the Bambara, Dogon, Jola, and Wolof communities, long experienced in rice cultivation. Their contributions of these enslaved West Africans included:

Farming skills: draining swamps, desalinating soil, and building levees.

Planting methods: flooded-field cultivation with controlled irrigation.

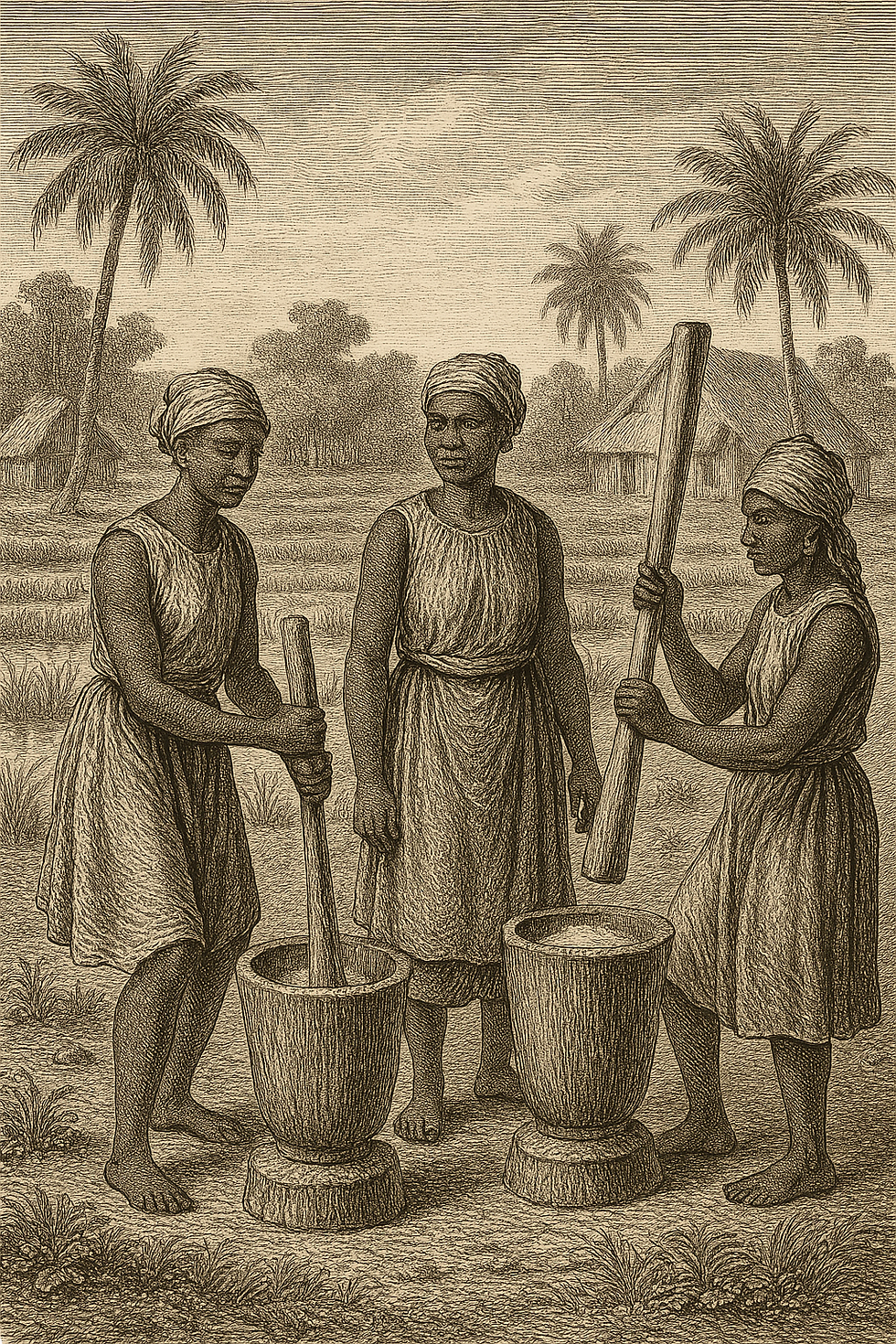

Processing techniques: creating nurseries for seedlings, pounding and polishing rice for sale locally and for export.

Both African Oryza glaberrima and Asian Oryza sativa were planted. African rice was hardy but fragile under mechanical milling, while Asian rice became more commercially viable.

Challenges of Rice Milling

Milling rice was notoriously laborious. Father Raphaël de Luxembourg, a Capuchin friar, wrote in the 1720s that it could take an entire day to produce enough rice for just two days of meals. Urseline nuns not working as educators were also required to mill rice and grind corn as their African and Indigenous slaves. Later, French company officials constructed two horse and wind powered mills using mechanical mortars and pestles. The mills cost more than eighty thousand livres to construct. The mills were also part of the company’s large plantation complex consisting of four thousand acres, one hundred and fifty slaves, a forge, blacksmith shop, brickyard, and hospital located on the west bank of the Mississippi River. Eventually, rice became a staple. By the mid-1700s, three-quarters of Louisiana’s population ate rice daily. Rice was even used as currency to pay for enslaved Africans.

Rice in Colonial and Antebellum Louisiana

Though central to local diets, rice never rivaled sugarcane’s profitability. By 1860, only nine planters grew rice commercially producing about 210,000 bushels in parishes like Bossier, Plaquemines, St. Charles, St. Landry, and St. Tammany.

Plaquemines Parish had the largest rice plantations, using levees and river floods much like in South Carolina and West Africa.

Subsistence farming: enslaved people often grew rice, pumpkins, corn, and sweet potatoes in swamps behind their masters’ sugar cane fields.

Providence rice: poorer settlers planted upland rice dependent solely on rainfall, similar to practices in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

By the mid-1800s, Louisiana planters shifted from African rice to Asian varieties like Carolina White and Carolina Gold, better suited to mechanical mills.

Rice After the Civil War

Rice remained a minor crop compared to sugarcane. Historian Olmstead noted that risiculture might have thrived if enslaved labor in New Orleans had been less costly.

After the Civil War, commercial rice production moved westward to Acadiana’s prairies. There, Midwestern farmers applied wheat-harvesting machinery to rice, reducing reliance on low-wage labor and transforming Louisiana rice into a modern industry.

Bibliography

Artaguiette, Diron d’. “Journal of Diron d’Artaguiette,” in Travels in the American

Colonies.” ed., Newton D. Mereness. New York: Macmillion Company, 1916.

Bérnard de la Harpe, Jean Baptiste. The Historical Journal of the French in Louisiana. ed. Glenn Conrad. Lafayette, La.: Center of Louisiana Studies, 1971.

Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo. Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Baton Rouge, La.: Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

Giraud, Marcel. A History of French Louisiana: The Company of the Indies, 1723-1731, vol. 5. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1991.

Lee, Chan. “A Culture History of Rice with Special References to Louisiana.” Ph. D. diss., Louisiana State University, 1960.

Mandelblatt, Bertie R. “’Beans from Rochel and Manioc from the Price’s Island’: West Africa, French Atlantic Commodity Circuits.” History of European Ideas 34 (2008): 411-423.

Penicaut, André. Fleur de Lis and the Calumet. trans. Richebourg Gaillard McWilliams.

Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1953.

“Rice Culture in Louisiana.” De Bow’s Southern and Western Review 21 (September 1856): 290-292.

Rowland, Dunbar and A.G. Sanders, ed. Mississippi Provincial Archives: French Dominion, 1729-1748, vol 4 and 5. Baton Rouge, La.: Louisiana State University Press, 1984.

Vogel, Claude L. The Capuchins in French Louisiana, 1722-1766. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America, 1928.

Wilkerson, R. “Production of Rice in Louisiana.” De Bow’s Southern and Western Review 6 (July 1848): 53-56.